Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture

May 5, 2019

After spending the night transiting back across the straits between South Korea and Japan, we landed the next morning in another port town on the northern tip of Japan’s southern island of Kyushu. Separated from the main island of Honshu by a very narrow channel, Kyushu is connected to it by a bridge and a set of tunnels that allow easy access back and forth between the two islands.

Mooring up in Kitakyushu was an easy choice for our ship as this city is one of Japan’s twenty designated cities, and a major hub for both land and sea traffic.

Snuggly moored up at the dock, we wait patiently for our transportation to arrive.

A relatively new city formed in 1963 by the merger of five independent cities, Kitakyushu is an important port for international trade, and has been a major centre for commerce stretching back to ancient times. It’s also a major industrial city that contributes greatly to Japan’s manufacturing sector.

Arriving in Kitakyushu

A very energetic assembly of drumming percussionists and their white whale mascot.

Like so many other ports in Japan, our arrival wasn’t missed by the local welcoming committee, and we were greeted with a musical display of large, pounding drums. Did I mention this was at 6:41 in the morning. Clearly the Japanese like to make an early start to the day. Us, well… not so much.

After a hardy breakfast and lots of coffee to energize us for the day, we had time before the tour buses arrived to wander down the long length of the wharf where we were docked. There were a good number of boats in all sizes and occupations from tugs to law enforcement, along with a decent number of local residents intent on catching a fish or two for their supper.

Akiyoshidai Observatory

A monument at the karst observatory. Very nice, but we don’t have a clue what it says.

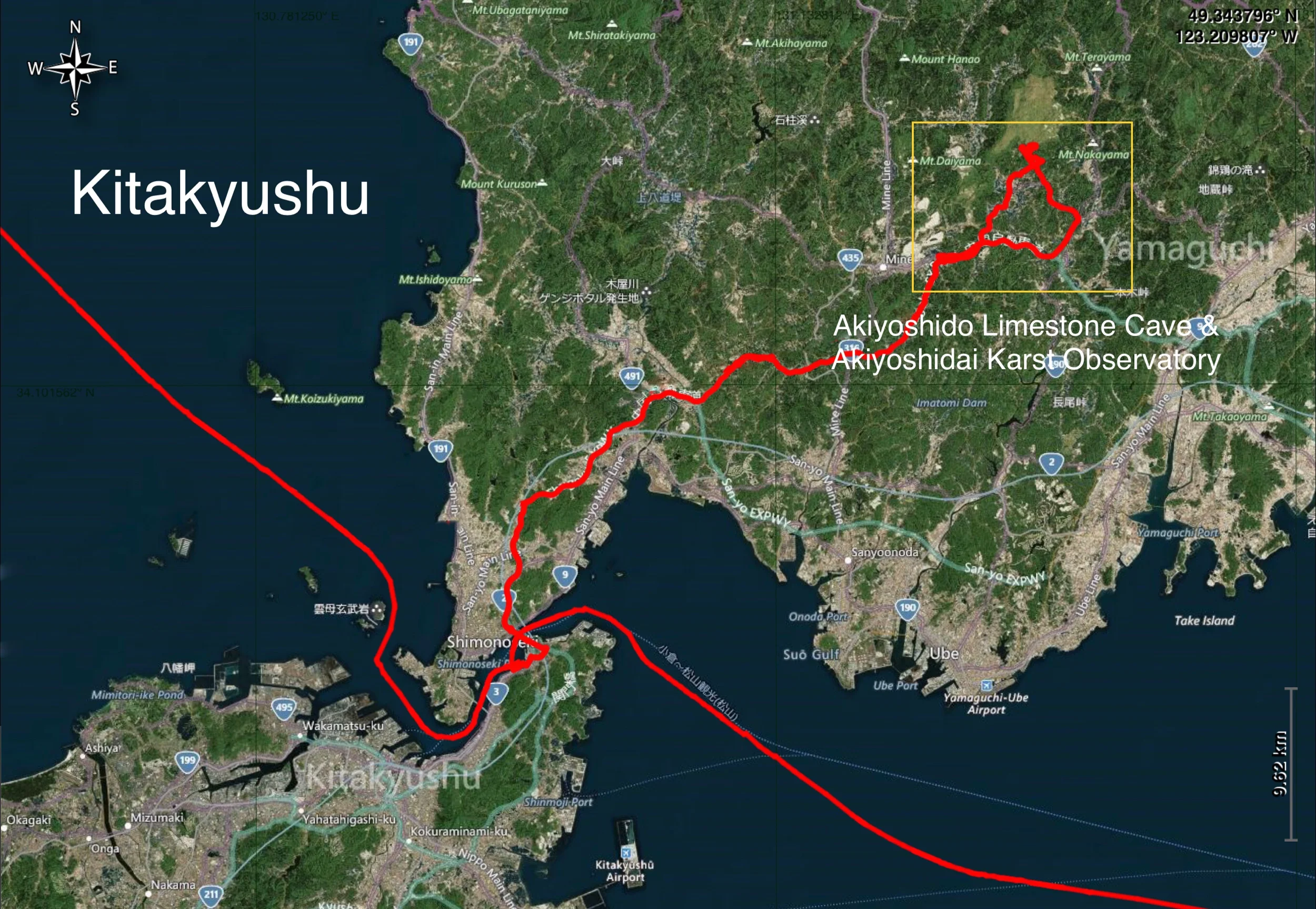

Although we moored in Kitakyushu, our focus for the day was actually over the bridge on the main island of Honshu. There we would be visiting the Akiyoshidai Karst Tableland Observatory and the Akiyoshido Limestone Cave, in Yamaguchi Prefecture.

The transit to the location in Yanaguchi Prefecture would cover a distance of about 50 kilometres, and along the way we would pass over the Kanmon bridge and drive by numerous towns and a host of farmland.

As vast as the karst tableland was, unless you were a keen geologist, the sight was a bit underwhelming. Essentially, the karst tableland was formed from limestone over a period of 300 million years, and over time it has been continuously eroded from rainwater. The result of this is the formation of approximately 450 subterranean limestone caves, the most notable of which we would visit later on during this trip. From above ground, however, uplifted jagged rocks set into a scrubby, foliage covered and hilly terrain seems to be what you get.

Akiyoshido Limestone Cave

One end of the cave system, which was actually our exit.

A short distance from the karst tableland was the entrance to the cave system we were to explore. Although the tableland was, in our opinion, not much to see, this vast cave was something entirely different.

This massive cavern is known to be the largest limestone cave in the Orient, and is located in what became the Akiyoshidai Quasi-National Park. Our walk this day would take us through roughly one kilometre of the 9 kilometre cave system, and would take us deep underground.

A pamphlet handout that you can get when visiting the cave.

Not dissimilar to Kartchner Cavern in southern Arizona, USA, which is another cave we have explored, this one differs from that one in a big way. Akiyoshido is relatively wide open and unrestricted to the quantity of people allowed to go through it. In other words, there are seemingly no environmental safety practices put in place.

This image is from the Kartchner Cavern State Park website.

In the Kartchner cavern, because is was discovered by two cavers who were surreptitiously exploring someone else’s private land, it was kept secret. Even the owners of the land, the Kartchners, didn’t know the cavern existed until the two cavers finally told them, and convinced them to donate the land to form a new state park. When it was finally revealed to the public, strict environmental policies had been put in place to protect the very fragile eco-system within the cavern. All openings to the cave were sealed, and a special door and hallway constructed so that when a group enters the cavern, they pass through a double door system that isolates the inside from the outside. Strict tour guidelines are in place, the lights are only turned on when you are about to view a certain feature (light causes breakdown of the delicate formations), and no one at all is allowed to touch anything, anywhere, at any time. You can’t bring anything into the cavern (not even a cellphone), and you can’t take anything out.

In the Akiyoshido Cave, it’s more of an open tourist curiosity. You buy your ticket, and then wander your way through the kilometre long boardwalk where you can read the various signs that explain what you are looking at. The lights are on all the time, you can have cameras to take photos, and there appears to be no environmental controls and no restrictions as to how many people can go through it. Mind you, the intricacies of the formations in this cave were nothing in comparison to the incredibly delicate formations in Kartchner. That being said, Akiyoshido Cave was still a very impressive natural formation to experience, and we were glad we selected this excursion.

Back at the Ship

A shot of our ship from the bus window as we arrived back from a very long day.

When we returned to the ship it was getting very late in the afternoon, and we just had time to grab a shower and get ready for a great dinner. Down on the wharf, the city hosts were setting up for a musical sendoff for us. Something that was a common occurrence for us in Japan. They really made us feel appreciated. The sentiment was very mutual, indeed.